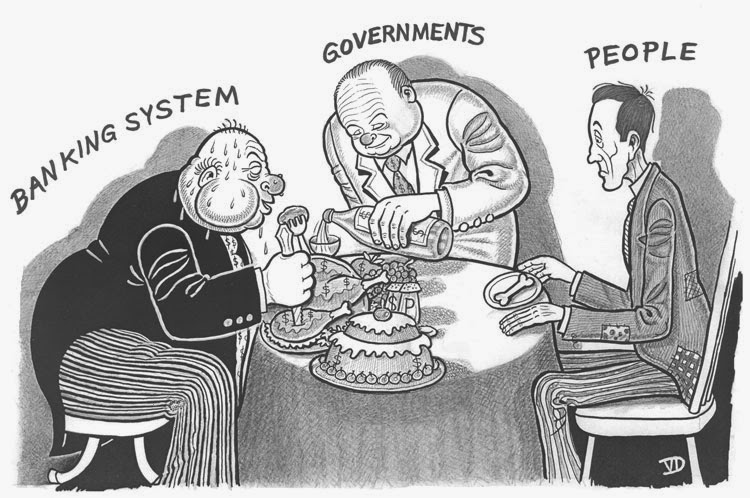

Bundesbank diz que bancos da Europa investem em títulos públicos e não no mercado e com isso a crise bancária e econômica na Europa se torna endêmica. É a velha história, dinheiro público vai para bancos que investem em títulos públicos, enquanto o povo fica desempregado.

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard escreveu sobre isso hoje, em um texto muito bom, mas um pouco contraditório, ao pedir mais dinheiro público nos bancos.

Bundesbank says Italian and Spanish banks still hooked

on home state debt

The Bundesbank always like to spoil the party. Tucked away on page 33 if its November monthly report is a reminder that the banking systems and sovereign states of southern Europe remain stuck in a vicious circle:

Italian banks have increased their holdings of Italian public debt from €240bn to €415bn since November 2011 (+ 73pc).

Spanish banks have raised their holdings of Spanish debt €166bn to €299. (+81pc). Ditto Irish banks, up 60pc; and Portuguese banks, up 51pc.

The EU summit pledge made in June 2012 to end this dangerous and incestuous linkage has come to little. As the Buba report said testily, "the mutual dependency of the banks and the state sector has grown most in those countries where the links were already particularly high at the start."

It is not a crisis as such. It is a chronic malaise. There is still an acute credit crunch for small business in Italy and Spain. The banks are hunkering down and living off their coupons from the state, even as the rest of the economy screams for credit. Their appetite for sovereign debt – boosted first by the ECB's €1 trillion long-term loans (LTRO), then by Mario Draghi's debt backstop (OMT) — is touted as a sign of recovery, but it is equally a sign of deformed EU policy.

Note too that these banks are buying the bonds of sovereign states where the debt trajectory is rocketing upwards, an effect made worse by Euroland's slide towards deflation. Italy's public debt has jumped from 119pc to 133pc of GDP since 2010, and average maturity has been sliding for two years as the treasury relies more heavily on short-term debt backed by the ECB. Spain's debt has risen from 62pc to 94pc. The longer the banks keep betting on this state debt, the greater the risk.

We heard this morning from the Bank of Spain that bad debts in the Spanish banking system have reached 12.68pc, the highest since records began half century ago. Loans under water have reached €188bn.

Daragh Quinn and Jaime Hernandez at Nomura warn that a number of Iberian banks look vulnerable under the Texas Ratio. This is the rule of thumb used in America's S&L crisis in the 1989 when 130 banks failed in Texas. The ratio is calculated by taking bad loans and property assets divided by tangible equity and total provisions. A ratio above 100pc typically leads to failure.

Nomura says the ratio for Banco Popular is 123pc (up from 109pc last year). Nationalised Bankia is off the charts of at 372pc. Sabadell is near 100pc.

As for Italy, the Banca d'Italia's Financial Stability Report this month says the banks are facing a "rapid increase in non-performing loans, principally to businesses, as a result of the protracted recession." Banca d'Italia warned that tensions could "resurface next year" as the ECB's three-year loans draw to a close.

Nothing has really been resolved. There will be a crunch in 2014 when the ECB carries out its next stress tests, with no proper EMU-wide backstop yet in place, or likely to be in place. Eurozone ministers agreed last week to "burden-sharing" rules that put investors in the front line for the first hit if there is a shortfall in bank capital.

Fair enough, but ex-ECB board member Lorenzo Bini-Smaghi says this risks repeating the sort of error made by Angela Merkel and Nicholas Sarkozy at the walk on the beach in Deauville, when they famously changed their minds and decided to impose a haircuts on holders of Greek debt (against vehement ECB advice) – without first putting in place any safety net to deal with the panic that was sure to follow.

The national governments will have to swallow the next layer of losses, if necessary with a loan from the ESM bail-out fund, even if they are dire trouble themselves and cannot safely take on more debt.

We don't know yet whether this burden-sharing (or bail-in) will be limited to junior debt, or senior debt as well as the Germans want. Nor do we know exactly what will happen to depositors (Cyprus again?), when push comes to shove. This is surely a recipe for trouble.

A monetary reflation blitz along the lines of Abenomics in Japan would make it a great deal easier to cope with this bad debt legacy. All the ECB has to do is to is target nominal GDP growth of 5pc a year (easily within its power) — or 5pc M3 growth, to mimic the effect – and a big part of the problem would disappear.

As I have written many times, the health of banking system and debt structure in both Italy and Spain is a simple mathematical function of the denominator effect. The higher the nominal GDP path, the easier it is to outgrow the debt burden. A real central bank can achieve this with a flick of the fingers. If it wants.

Italy and Spain are formidable countries. They are entirely savable within EMU under expansionary policies, yet all too easily lost under contractionary policies.

If I were an Italian or a Spaniard, I would have a few caustic words to say about the Bundesbank's report today. Had Frankfurt not pushed for two premature and destructive rate rises in 2011, and had it not opposed any pre-emptive stimulus over recent months to avert incipient deflation, and had it not let eurozone M3 money growth go negative over the last five months, the banks in Italy and Spain would now be in far better shape.